Sunday on CTA Route 49

Over here in Illinois a coalition of powerful and dangerous people and organizations seems to be supporting a “transit future” initiative to harvest a “robust revenue stream,” inferentially a further increase in the sales tax. I say “seems to be” because I haven’t verified that everyone listed (including southern California’s moveLA) is in fact a supporter rather than a typo. And “inferentially” because the examples cited on the site involve sales tax increases.

GETTING TO HYDE PARK…

There is some fancy mapping at vision.transitfuture.org (I can’t afford a fast enough Internet connection to make this run smoothly, and I had to disable some security to run it at all) which seems to include a version of Mike Payne’s Gray Line proposal. It is claimed that this “would connect Chicagoans to 50,000 jobs in Hyde Park,” as if the Metra Electric and existing CTA express bus service does not do so. I also wonder where the 50,000 figure comes from, as the total for four zip codes (60615, 60637, 60649, 60653, an area far exceeding what most of us consider “Hyde Park”) as of 2013 was only 37,158 (government and self-employed excluded). I do recall Mike Royko’s conclusion, many years ago, that Hyde Park is in fact part of New York, not Chicago, so I guess the “connecting Chicagoans to Hyde Park” concept might make sense.

…AND ELSEWHERE

Of course the proposal includes something for everyone who matters, including arterial express buses (not a separate lane, but some priorities) in the suburbs, but no mention of how transit-unfriendly but job-rich office and industrial parks are to be served. There are also expenditures for maintenance and rehab of some of the existing rail infrastructure. The once-proposed Crosstown Transitway is resurrected as the “Lime Line.” Ashland BRT is there, but there seems to be no consideration of the much less costly (and much faster to implement) option of reinstating and expanding CTA’s limited-stop bus line experiment on Ashland and other arterial streets. They say that “Now everyone can get to school—and to the hospital,” both of which we already could do, and there’s no mention of how we will be able to afford to make use of either once we get there.

The ill-conceived Red Line south extension is included, and the map implies that Metra Electric will be truncated at 119th and all northbound passengers required to transfer to the Red Line if they want to get downtown. “The Red Line extension will cut commute times to the Loop,” but the fact is Metra Electric routinely runs from 115th to Van Buren in 23 minutes while the newly-rebuilt Red Line with new 5000-series cars takes the same amount of time from 95th to Harrison. Certainly a Red Line extension could quicken some trips for riders south of 95th without requiring payment of a Metra fare, but it’s hard to believe that it wouldn’t be cheaper for the public and better for most riders if Metra service frequencies were improved and fares included in the CTA system.

And there’s more, including some or all of the CREATE project, and an extension of the Brown Line to Jefferson Park (I wonder whether the community would prefer an elevated line clattering above the street, or a few years of chaos while a subway is dug, or even more picturesquely, a surface-level train with numerous grade crossings.)

FUNDING THE PROJECTS

Regarding funding, transitfuture says:

Los Angeles is doubling the size of its transit system. How are they paying for it? In 2008, Los Angeles residents voted to raise LA County’s sales tax by just a ½-penny.

The result: $40 billion for new transit lines.

So, including the 1/2-cent transit tax, LA total sales tax is 9%. In Chicago, it’s 9.25%, with extra charges on luxuries like fast food and soft drinks. And L A exempts groceries, on which Chicagoans pay 2.25%. So transit future seems to be asking us to pay a lot more than L A does.

In any case, transit future says its proposals will cost $20 billion (who knows where that figure came from?). The latest retail trade figure I can readily find for the eight counties (Cook, DuPage, Grundy, Kane, Kendall, Lake, McHenry, Will) which might make up a transit service area is $116.660 billion. This is for 2007, and presumably includes everything which would be taxable by RTA (who must have a later figure but do not make it prominently available). A 1/2% sales tax would yield far less than a billion dollars/year, not enough to service $20 billion in bonds even at a favorable interest rate (and this is not even mentioning the likely increased operating subsidy which would be required.) And the transit future web site mentions merely that

The Cook County Board of Commissioners can create a robust revenue stream to fund the construction of these new train and bus lines. This local revenue will open the door to federal and other financing tools that will pay for the rest. Transit Future is a campaign to convince the Cook County Board to create that local revenue stream—and to do it this year.

So, the forces behind transit future do not expect local funding to pay for the majority of their capital desires. (And, with nine of the County’s 17 Commissioners already listed as transit future supporters, it seems they shouldn’t be difficult to convince.)

MAGIC FEDERAL FUNDING, ENRON-STYLE

Elsewhere transit future says

A new revenue source will allow the County to take advantage of America Fast Forward and other financing tools at the federal level.

So here is something else new to me, America’s Fast Forward. This seems to be a big deal, California-based, with a website much easier to navigate than transit future’s. Recognizing the overwhelming size of the Federal debt and deficits, they have contrived a scheme that not only better hides the Federal expenditures to support transit, but also provides more opportunities for the involvement of the finance cartel. If I understand this pdf correctly, they want to replace direct Federal subsidies and tax exemptions with tax credits. A state, or locality, will issue bonds, and affluent investors will buy the bonds. There may be jurisdictions with lots of bonding capacity who could take advantage of this, but I would think Illinois or Cook County (or Chicago) would not want to add to their debt burden, with possible further damage to their credit ratings. Anyhow, the special feature of these America Fast Forward bonds is that the borrowers would not pay any interest. Nor would the federal government pay any interest. Instead, the federal government would provide a tax credit, which seems economically the same as interest but does not show up as part of the federal debt or deficit. A further advantage, for some of the supporters (such as investment bankers), would be the opportunity to market a new kind of financial product on which fees can be “earned.”

THE INTERESTS BEHIND IT

There is a short list of “supporters” here, with longer lists of “labor” (unions) who would like to obtain income for their members and officials, businesses who would like to get contracts (and, for some reason, a brewery), and a “community civic” category who includes some of the traditional grant recipients as well as local groups advocating for specific areas. Curiously, much of the design of Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corp’s web site seems to mirror (or model) that of transit future.

WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

So the purposes of transit future and America Fast Forward (whose supporters can be inferred from information on their site altho I didn’t see a consolidated list) appears to be to generate revenue for the benefit of their supporters, which is to be done by increasing taxes and manipulating the federal funding methods to do something like increasing debt. In order to sell this, and because a few of their supporters may want it, they are proposing transit-supportive capital expenditures with no evidence of how the operations are to be funded. Transit riders might prefer a more rational approach.

In an ideal world, transit improvements would be funded 100% locally, via a land value tax which is borne entirely by the beneficiaries of the service. Unfortunately, landowners have found that funds from other sources can be obtained, and therefore oppose paying their share. To the extent federal funds are available, the game changes from “How can we improve access?” to “How can we obtain some of our region’s tax money back and use it to benefit those who help us?”

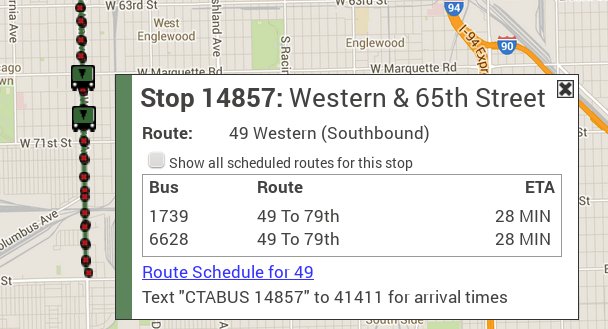

A region that has huge amounts of vacant sites with easy access to transit service should be focused on ways to make effective use of those sites. People living in “transit deserts” deserve transit service as much as the rest of us do, and a considerable percentage of the population chooses to relocate every year, so we should ask why they are not relocating to areas where both vacant land and transit service are available. Knowing the answer to this question, policymakers can decide how best to use public resources. This might involve improvements in existing services (such as faster and more frequent Metra service, limited-stop buses with priority), some service expansions, and improved management. Modern tools which allow me to see two buses following one another down Western Avenue, while leaving a 28-minute service gap behind, also would allow competent, credible management to fix the problem.